Case Study

Defeating “Personhood” in Mississippi

New Jersey is the nation’s most urbanized state and has been using public money to buy open space for more than 50 years. However, with the state in $40 billion in bonded debt, all environmental and conservation funding had run dry.

Pundits, political experts and the national media couldn’t resist assumptions that Mississippi voters would pass “Personhood” without pause. In a state where 78 percent of voters call themselves pro-life, the prevailing wisdom was that Initiative 26, which became known as the “Personhood Amendment,” would easily prevail. Boy, were they wrong.

The initiative stirred instant passion. If passed, it would have amended Mississippi’s constitution to define life as beginning at “the moment of fertilization” and would have marked the greatest restriction of reproductive rights enacted in any state, ever. For pro- life activists, it was a shot at setting a precedent they hoped could reverberate through states all across the country.

For those tasked with defeating the effort, the deck wasn’t exactly stacked in our favor. Every state- wide Democratic candidate came out in support of the amendment—just to play it safe. Most other public officials did the same. The groups with the courage to speak out were the Mississippi Doctors and Nurses Associations, the NAACP, the Mississippi chapters of Planned Parenthood, and diverse groups of clergy and coalitions of mothers, husbands and wives.

On a relatively sleepy off-year Election Day, Mississippi voters sent shock waves through Washington, D.C. and shattered the conventional wisdom in rejecting the initiative by an astounding 58 percent to 42 percent margin. More impressively, voting to reject Initiative 26 tracked closely with the support for newly-elected Republican Governor Phil Bryant, indicating the presence of a broad coalition of voters who came together to soundly reject government intrusion into personal health care decisions.

From the start, we knew winning in Mississippi would require directing a nuanced and focused message to the right voters within the state’s largely conservative electorate. Given the demo- graphics, relying solely on the strength of a motivated Democratic base wasn’t an option.

We got the green light to move forward with the campaign 55 days out. On September 14th, Democratic media consultant Sarah Flowers, the political organization 76 Words, and I arrived in Jackson, Miss. to put together a campaign structure, staff, team of consultants and plan. As co-general consultants to the campaign, Sarah would produce the television and radio, while my firm — Wampold Strategies — would produce direct mail. We were also fortunate to hire Jonathan Levy as campaign manager, who’s proving to be one of the best managers in the country.

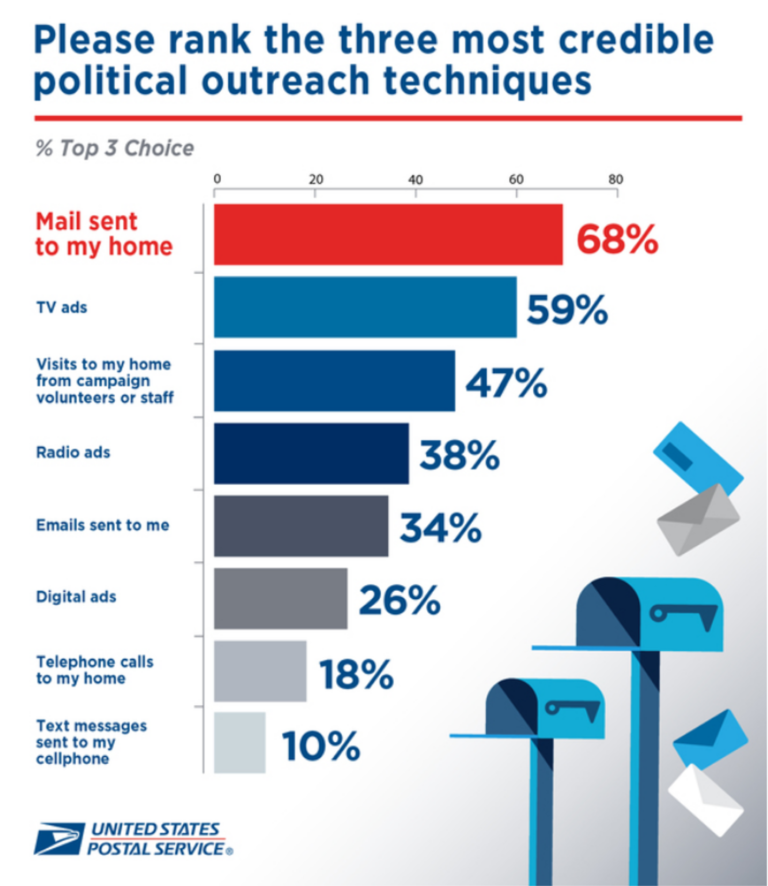

The campaign plan was modest and was definitely a working document. Our initial plan relied heavily on direct mail to white suburban women, chronic African-American households and Democratic primary voters with a limited TV buy in the Jackson media market. Paid phones would support our message in the mail. A limited field plan would add volunteer phones and very little canvassing.

But as the campaign gained momentum, additional fund- raising and other efforts allowed us to significantly increase our TV buy across the state. We were eventually able to make a buy in the costly Memphis market. Television became the primary medium to communicate with women voters, while mail and phones focused African-American support and a wedge universe of white men. Eventually, paid phones would contact all chronic voting house- holds with messages targeted to all of our primary audiences.

THE ‘NO’ ADVANTAGE

The starting point on Initiative 26 was the understanding that ballot measures fundamentally differ from candidate races in that we’re asking folks to vote up or down on an initiative rather than choose a representative. Only one side is truly charged with persuading voters to vote in favor of the measure, while the other side is simply convincing voters it’s a bad idea.

Mississippians for Healthy Families employed this fundamental strategy by framing Initiative 26 as not in line with Mississippi values, a threat to the health of Mississippi families and a costly expansion of government involvement in our personal lives.

Cornell Belcher and Dan Martin of Brilliant Corners conducted the baseline poll that laid out the path to victory. There were no silver bullets, but we framed our case against Initiative 26 as “government going too far” with serious “unintended consequences.” Arguments about a threat to women’s health and potential economic costs in a poor economy softened support for personhood and moved voters away from a “yes” vote.

Not surprisingly, a solid majority of Mississippi voters call themselves conservative, including 50 percent of African-American voters. Further, 66 percent of all voters attend church at least once a week, and only 22 percent are truly pro-choice. A full 84 percent of African-American voters call themselves pro-life.

The initial ballot test showed opposition to Initiative 26 at 37 percent, with 26 percent strongly opposed. The encouraging news was that support for the amend- ment was below 50 percent, and another 16 percent were undecided. After hearing arguments for and against the measure, we were able to increase opposition to 46 percent in the informed ballot question. We were pleasantly surprised to find a softening of support for Initiative 26 across all demographic categories. It showed us that voters were concerned enough about the consequences of passing 26 that they’d consider rejecting the amendment.

Our strategy was basic: give voters pause, use language that takes them into their own experience, recruit locals to deliver our message and focus squarely on the health of Mississippi families.

EMBRACING A CONSERVATIVE MESSAGE

We had to find a way to move the conversation away from abortion to have any chance of defeating Initiative 26. By framing the argument against 26 as “government going too far,” then focusing on the unintended consequences, we believed enough voters could be convinced to reject the initiative. The tricky part was striking a chord that would essentially allow conservative voters to oppose 26 without feeling as though they were abandoning their value set.

To that end, we focused on four key constituencies:

- White Women: White women were the primary battleground for both campaigns. Women were much more entrenched in their support or opposition than other targets, but splitting the vote of white women was critical to holding support for the initiative below 50 percent.

- African-Americans: Black voters were the biggest movers in our polling, and a winning margin of two-to-one here was essential to defeating 26.

- Chronic Democratic Primary Voters: Preventing drop off from this small but important group was a primary goal. We had to bank every pro-choice voter and chronic Democrat to meet our vote goal.

- Moderate White Males: Polling showed huge movement among white males from support to unde- cided, suggesting a potential for drop-off. Messages about govern- ment intrusion and health risk for women also tested well enough to target as a wedge universe.

Once we identified our targets, we zeroed in on message. If we were going to succeed in convincing voters to oppose personhood, discipline would be critical. The only way we could keep control of the message would be to make no mistakes, particularly given the national media attention on the initiative. Sparking a national debate on “choice” would bring the conversation somewhere we did not want it to be.

Our message triangle centered on the broad position that Initiative 26 is an example of government going too far. We then decided to focus attention on the health risks for Mississippi families, the economic costs and the notion that Initiative 26 was out of line with Mississippi values.

Among our core emphases: Initiative 26 threatens the lives of women, potentially forcing a woman to carry a pregnancy even if her life was in danger. The proposal was so extreme that it would ban common forms of birth control and in-vitro fertilization, making it harder for women and men to plan their families responsibly.

On the values question, we framed it this way: we all want to reduce the number of abortions, but 26 just goes too far. It would force a woman who was raped, or the victim of incest to carry a pregnancy caused by her attacker, forcing her to relive the horror of her attack every day. In addition, 26 is so poorly worded that it puts us all at risk. If you cause a minor accident and a woman has a miscarriage, you could face manslaughter charges. If passed, we argued, 26 would be a bonanza for trial lawyers.

Voter concern over the economy served to amplify our message. We argued that government should focus on getting the economy back on track, not finding ways to meddle in personal health care decisions. Mississippi already spends more than $155 million a year dealing with teen pregnancy. Right now, we simply don’t have the money needed to fix roads, educate young people or keep Mississippians healthy.

The key was that we never asked voters to abandon their morals or value set in making the case to oppose 26. We first hoped to give them pause, move them away from the emotional issue of abortion, and then focus on the unintended consequences of the initiative.

IMPLEMENTING THE STRATEGY

Our first TV ad featured a testimonial from a rape victim who discussed the torment of having to decide whether to carry her attack- er’s child. The testimonial navigated through the moral struggle. It concluded with a powerful line delivered direct to camera: “It’s okay to be pro-life and vote No on Initiative 26.” More than any other statement, it exemplified the permission voters were looking for to oppose the amendment.

Our direct mail strategy focused on two target universes: African-American households and white men. Our general messaging tested well with both, though white men were more responsive to the argument of government going too far.

Post-election research showed that 49 percent of white men voted “no,” proving them to be an effective wedge universe where we not only reduced margins but split the vote of a notably conservative audience.

The phone program was run by Brad Chism of Zata3, a national consultant based out of Jackson who, in addition to paid phones, brought a deep knowledge of Mississippi politics and voter tendencies. Our initial campaign plan budgeted for a solid phone program in concert with our direct mail. Successful fundraising and late money allowed us to add paid phones to supplement our volunteer ID calls.

Calls to our wedge audience of white men were extremely effective, especially after Governor Haley Barbour’s public pronouncement that he had serious concerns over the potential consequences of 26. Barbour offered our effort a lift less than a week before Election Day. Appearing on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe,” he admitted he had “serious reservations” about the potential consequences of 26. Though he announced the next day that he had in fact voted “yes,” his earlier admission amplified our campaign’s main message.

We quickly took footage from the Barbour interview and aired it in a new ad placed in markets to reach rural Mississippi voters. We also used it in robocalls to rural white voters.

It was clear that our opposition intended to remain focused on anti-abortion messaging and decrying the outside forces of Planned Parenthood and the ACLU. Their assumptions proved to be fatal. While they were focused on demonizing others, Mississippians for Healthy Families was busy forming coalitions of doctors, nurses, faith leaders and many other groups who found their activist voices for the first time. These groups offered us the local voices we needed to counter the yes campaign’s claims that we were nothing more than a coalition of out-of-state organizations concerned only with a national agenda.

The Yes on 26 campaign put all of their eggs in one basket with an expose on Planned Parenthood that fell flat and even backfired with the media for their dismissal of the potential consequences of the amendment as political gimmicks and tricks. After that, the media largely focused on the threats posed by the initiative and the momentum had swung.

By Election Day, there was cautious optimism. We had managed to implement a plan that no one thought would come together so quickly and effectively. We now had a GOTV program that had expanded beyond a few key urban areas and college campuses to become a massive field and phone program. We had television in all but a handful of counties, a fully funded mail program and an absolute domination of earned media.

Still, no one dared make predictions and we braced ourselves for the reality check we believed was coming after the polls closed. We were tracking evenly with the returns for Republican Phil Bryant, who was leading Democrat Johnny Dupree by double digits, but no one dared breathe a word until shortly before 10 p.m. when it was announced that Initiative 26 had failed to pass. Then there was jubilation.

A PERFECT STORM?

Was this victory the result of a well-executed campaign plan or was it the result of a perfect storm in a unique set of circumstances, events and an off-year election?

I would say both. There is no denying that the off-year election cycle gave us the opportunity to focus national resources in one campaign and that was an advantage. In 2012, there could be as many as 15 personhood measures on the ballot in states across the country. The campaign also benefited from an election cycle with very few contested elections, demanding voter attention. It also left the local press with little else to talk about and an over-confident opponent who assumed the race would be a lay-up in a conservative Southern state.

However, the fundamentals of winning campaigns—especially ballot measure campaigns—still applied. You play the cards you’re dealt, you execute the plan based upon the collective factors of the state or district, and then you capitalize on the opportunities that present themselves.

The way we framed the race and approached the strategy is a blueprint of sorts for campaigns facing similar challenges in off- year races.

- We took advantage of our position as the “no” campaign to raise doubts, concerns and talk about the threats of the initiative.

- We developed a realistic campaign plan based upon the resources we had available, while allowing for the flexibility to enhance or make corrections to the plan without abandoning the fundamentals.

- We made smart decisions as new resources became avail- able, and we found traction with our messaging.

- We controlled the dialogue with message discipline and spokesperson training to avoid the pitfalls and divisiveness of the issue of choice.

- We found common ground with target audiences to give them enough pause to consider the flaws in the Initiative and the unintended consequences.

- We capitalized on the mistakes of our opponent, and we seized opportunities as they presented themselves—in this case with earned media, outreach and a surplus of volunteers.

In the end, we won this campaign because Initiative 26 would have been a bad law with far reaching consequences that outweighed the commitment of Mississippi voters to protecting the unborn and their pro-life position. We effectively communicated these concerns in the proper tone without asking voters to abandon their value sets. In the process, we won over a heavily conservative electorate and dealt an early defeat to anti-abortion activists ahead of a presidential year that’s sure to see plenty of similar ballot initiative battles.

Your campaign is too important to hand to an inexperienced firm.

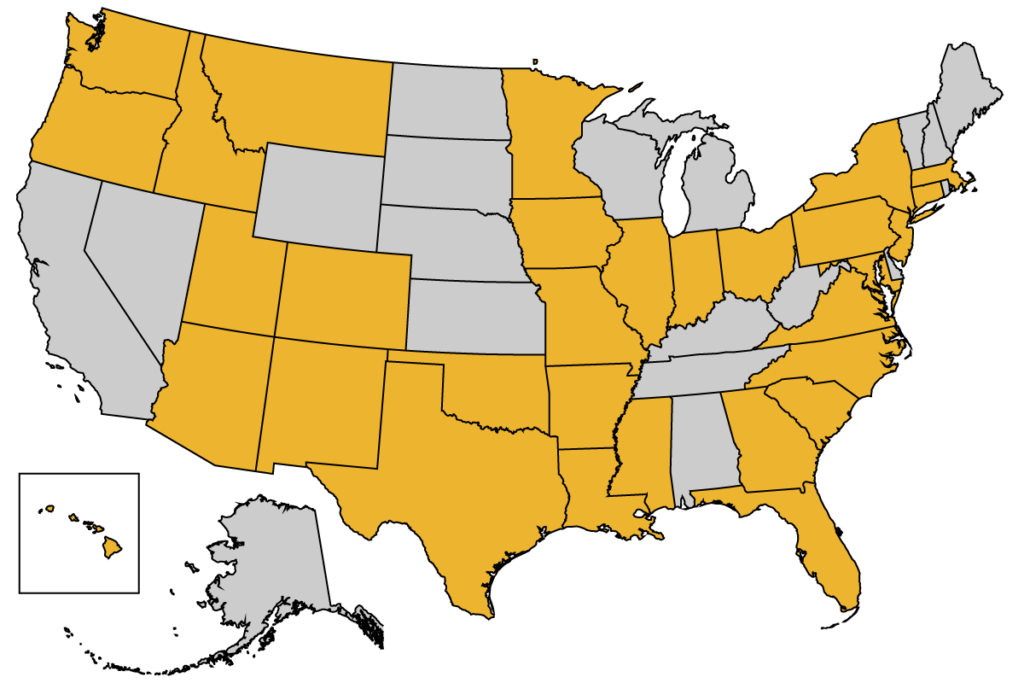

We have won elections in 31 states, electing Democrats, and securing billions in funding for progressive causes.